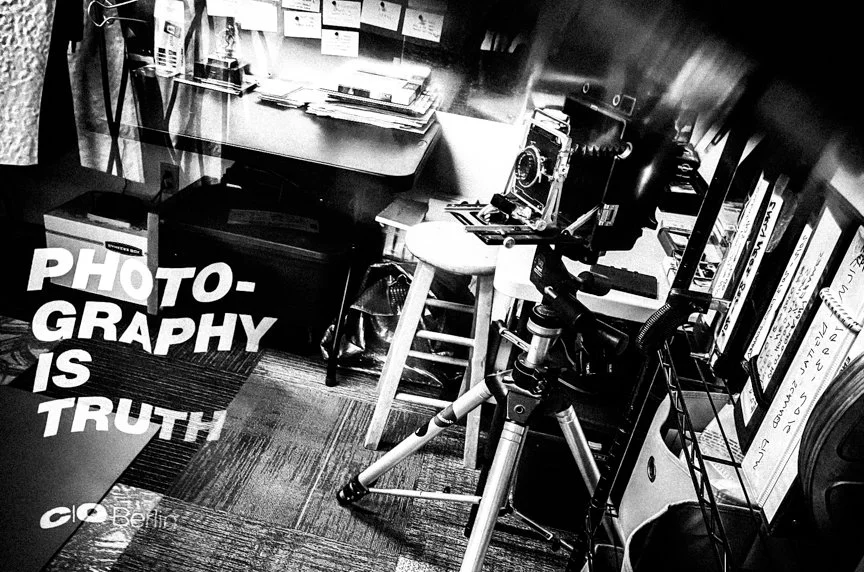

I spend most of my days in my studio. This is the benefit of remote working. As long as my laptop is open, emails rolling in, numerous Zoom meeting, etc… I am “on the clock.” The advantage of having all of my art supplies readily available is a blessing and a curse. My studio space resembles my brain in many ways. Sometimes I need to turn it off, which in this case means randomly pulling “work in progress” off the walls, so I can stop thinking about THE WORK for at least a little while. The upside of working in this environment is that I can dabbler with an idea at anytime, and garner quick results, via Lightroom and my decent Canon printer. Case in point, I got a bug up my ass yesterday about my ongoing boredom with “straight” photography. At the same time, complete abstraction seems too easy sometimes, or just a plain, self-indulgent mess other times. The problem (not really a problem) with photography in general is that it seems so intrinsically tied to the real world (broad generalization, I know.) Somehow, someway, reality need to peek it’s head into the camera, and onto the subsequent print, or else it drifts into something else, something (primarily) non-photographic. I’ve taken to shooting through prisms lately (as seen last year in full effect in Paris) and I think what I like about the approach (when it works…and often it doesn’t…) is that it breaks just enough from reality, and falls into the territory of “uniqueness.” Reflections and transparency wielded in a barely controllable manner, with a heavy helping of serendipity. It reaps non-repeatable results, for sure. Images that are only by me, for better or for worse. Even dabbling in the studio becomes a journey into unknown territory, and as the above image can attest, sometime the results are magic.

A view through a prism; May 2024