Portraiture has always confounded me. As a photographer, I’ve struggled when I’ve had to deal with actual human beings as subject matter. Especially when they are directly in front of me, posing for a formal portrait. I am just unable to capture the essence of a person through a photograph. That’s not to say that I don’t ever take pictures of people. It’s just that they tend to be in an environment, usually on the street, or part of a larger, more complex scene. At the same time, as a viewer, I am constantly drawn to a great photographic portrait. Needless to say that our western pop culture is awash in portraits, many focusing on those in power, or those with celebrity. Add to the mix the current frenzy of selfies clogging up social media platforms, and one could deduce that perhaps we’ve hit the breaking point where the whole idea of a photographic portrait has transformed into something other than a thoughtful study of not just the appearance of the subject, but also a deeper exploration of their mood, their character, their psychological makeup. Most portraits today, to my eyes, seem more self-aggrandizing, self-serving; propaganda mechanisms more than anything else.

With this cynicism in mind, I focus my gaze today on a most beautiful portrait. Titled “Black Eye” it is by a true American master, Sally Mann. Sally Mann has made a career of photographing her immediate family, most notably her children. This approach has brought her much acclaim, but also much criticism. The critics are usually from outside the photography / art worlds. The puritanical, religious “moral police” that exists in the United States have, on numerous occasions, worked themselves into a foaming-mouth frenzy over the intimate work of Mann. Their objections are almost always due to the fact that Mann has no reservation for showing her (then) young children, both male and female, in the nude. The rabid critics have dismissed the work and pornographic at worst, exploitative of innocence at best.

The image I am discussing today is of a fully clothed child, the artist’s daughter, but still has been cause for alarm by many narrow-minded critics. More on that in a few moments. Let’s take a closer look at the photograph. It is a black and white image. A young girl sits in an antique looking chair, and is positioned squarely in the middle of the frame. Her eyes are closed, her arms are crossed. She is bathed in wonderful, soft natural light, coming from a window that is in the distance, the edge shown in the photo, out of focus. The hair on the girl looks like it has been blown to the side by a sudden soft breeze. The focus on this image is interesting to me. The detail on the white lace below her neck indicates a shallow depth of field. The hair and chair shows a varying degree of focus as well. The curls of hair along the lower neck is a foil to the unkemptness of the blown hair along the top of her head. Her hands are crossed, but at ease, and they look as though they are cradling something. The wonderful downslope of her dark lips brings a certain melancholy to her appearance. And then we have the black eye. How did this happen? The zealot critics have projected evidence of child abuse onto the photo. But as we know, kids get all sorts of bumps and bruises while the explore their world. And I can help but think that her eye looks swollen due to a bug bite. Especially when you consider that Mann and her family live in rural Virginia, there are all sorts of reasons a child might be sporting a swollen, black eye.

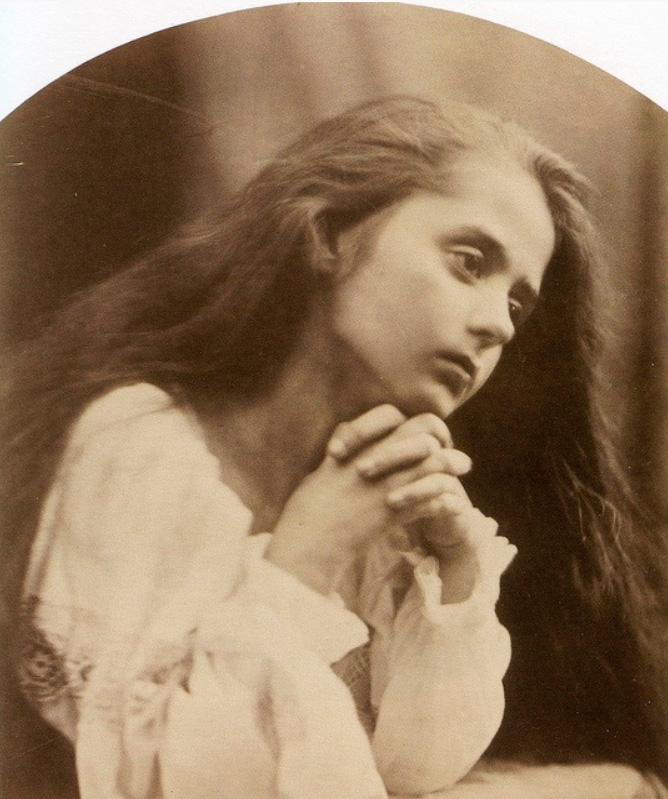

Photos by Julia Margaret Cameron

What I find most striking about this image is its timelessness. It looks like it could have been made in the later 1800s, and reminds me of the work of Julia Margaret Cameron, with its references to Pre-Raphaelite painting, featuring limp poses and soft lighting. Mann’s photo has the same qualities. The young girl’s dress furthers this timeless atmosphere, as does the chair she sits in. The photographer has captured not only a very intimate moment, but has, though her craft, imbued the image with so much psychological power. The photo not only seems to represent a girl lost in a dream, but also feels like a dream itself. And if I dive further in the subconscious elements seen here, I could also see this as a death portrait. Her eyes are closed, her hands are crossed. Is she laid out in a coffin? Is this a display, not only to the fleeting nature of youth, but the ever present spectre of death? Now consider that this photograph was taken by the girl’s mother. The sense of serenity is one that a mother would probably know better than anyone, when seeing your young child asleep. But isn’t also a parent’s greatest fear, the death of their child? Is Mann exploring this fear with her camera? Is she challenging the viewer to take stock of their own familial relationships? Could a stranger had been able to create such a powerful image of the same young girl? I doubt that the kind of gentle touch of the artist’s lens, the intimacy of the space, the softness of the light would be available to an outsider.

It is a sad fact that women are underrepresented in the arts, and photography is no exception. Men have most times taken the spotlight as innovators, or as the heroic masters of the art world, and certainly this holds true in photography as well. But it is the work of Sally Mann that proves the value, the legitimacy and the true artistry that a woman artist can possess, and should rightfully be recognized for. I would highly recommend reading Sally Mann’s autobiography, “Hold Still.” Her family history certainly informed her artistic development, but it’s also a wonderful look at the creative process of a true photographic master.