I’ve been treading lightly in regards to selling my work. The truth is, most people don’t buy art. They don’t value art. They don’t see a place for art in their homes, in their lives. Money for rent, for a car, for food, for health insurance, for a vacation, for drugs… all on the list way ahead of art. Still, we live in this god forsaken capitalist society, where everything (and everyone) has a price tag. To be an artist in this environment is a challenge. To keep the dirty concept of money out of my art has been a struggle. I don’t make might art to make money. I’ll do it anyway. But… material costs money. Internet and websites cost money. My studio (a luxury, I know) costs money. Hanging a show costs money. Prints and frames and promotion cost money. Again, sales of artwork are few and far between. And yet… I can’t deny that it is nice to make a sale every now and then. It is validation, for sure. Someone likes your work enough to pay for it. To hang it in their home. To live with it. I don’t want to be motivated be profit, or greed, or even breaking even. But somedays (like today) it is hard. Hard to justify making work to sell. Hoping to move a few framed photos. The adage that “nobody cares about your work” still is a tough thing to hear and every now and then, you get a stiff reminder of the truth in the statement. I have been working on adjusting my attitude towards “selling” and I am trying to divorce myself completely from the expectation of getting money for something that comes from so deep inside of my soul. The art vs. commerce dilemma is nothing new, but it’s jarring when the sludge of money creeps into my process. How do you feel?

Manifesto

A few months back I wrote up a list of my creative beliefs. These were relevant only to me, and only for that given moment. The more I sat with the list, and let it gestate, the more I liked it as a sort of ad hoc manifesto. You know, all the great movements seem to have a manifesto. Karl Marx had his; Martin Luther nailed his to the church door. The Situationists, the Dadaists… hell, even my therapist helped me focus on a Dharma code…a spiritual, intention focussing manifesto, so to speak.

I have this current manifesto stuck to my studio wall, and also have it as my laptop wallpaper, so I look at it on a regular basis. I incorporated different influences; some from improv, some from my therapy, some from my art studies, and some from my rage and depression (if I’m being 100% transparent, which I am…)

I thought I’d share it here, in hopes that it pushes you, dear reader, to consider your own creative, personal, expressive values.

Some thoughts on each:

“Inactivity is not laziness.” There is great value in doing nothing, and if given the time and space, to do nothing for as long as possible.

“Destruction is creation.” I cribbed this from Picasso, thought I think it is a biblical idiom originally. It really rings true for me, especially in regards to my art practice over the past couple of years.

“Give things away.” Sharing my thoughts, my words, my blog, my podcast, my zines, my photos is an integral part of my interaction with my muse and with my world.

“Expect no reward.” Money, fame, and validation are all fine and good, but I try to create (and to live) with no expectations of profit, monetary or otherwise.

“Expect no audience.” No one gives a shit about you and your artwork. Make it anyway.

“Make boredom valuable.” Much of life is underwhelming, if not outright mind-numbing drudgery. Use this reality as fodder for thinking of things to create.

“Make something every day.” Take a photo, write a note, sing a song, bake a loaf of bread. One creative act a day keeps the wolves at bay.

“Remain curious.” Hard to be bored when there is wonder all around you.

“Say ‘Yes, and…’’ ” As in improv, so in life. Agree and add to other ideas. Saying “no” ends all potential immediately.

“Be the ‘you’ the world needs.” A bit woo woo, a bit snowflakey, but I don’t care. You were born, you’ll die. Be the best version of yourself you can be.

“Live until you die.” Like they say in Shawshank Redemption…. Didn’t realize it was a Stephen King quote.

feel free to snag this image for yourself…

Worth A Thousand Words: Ansel Adams

Preface: For those of you who followed my “Worth a Thousand Words” series, you know I usually focus on one specific photograph by a photographer and then take a deeper dive, exploring not only what the image shows but also what the photographer may have been trying to tell us, or have us think about. But for this installment, I’m going to try things a little differently and talk about one photographer and his work (and reputation) in a more general sense. Warning: some of my words may be perceived as inflammatory or disrespectful or antagonistic, all of which may indeed be true.

The God of sharpness, perfect exposure, cable releases and beard grooming

Photo credit: J. Malcolm Greany, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

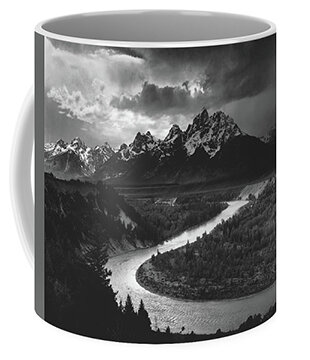

Today, I’d like to discuss the work of Ansel Adams. He is most likely the most well-known photographer in the history of the genre. He is held in high regard by many people, photographers and non-photographers alike. His work can be seen in many formats: not just impeccably printed photographs framed on a museum wall but also in books, calendars, postcards, coffee mugs, refrigerator magnets… I could go on, but I’ll stop there. My motivations for discussing Ansel Adams is rooted in a paradox in my own mind regarding his importance to the art form and his position in the canon of the fine art photography.

I won’t go too deeply into his biography, you can head over to Wikipedia for that. Instead, here’s a list of his achievements. I’ll mark the ones I have a problem with using my newly patented star system.

One * means… a-ok or not so bad.

The more ****s, the more something bugs me.

Ansel Adams was an American photographer and environmentalist, known for his black-and-white images of the American West. *

He was a life-long advocate for environmental conservation *

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980. (from Jimmy Carter, so that’s cool.) *

Adams was a key advisor in establishing the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an important step in securing photography's legitimacy. *

He helped found the photography magazine Aperture. *

He co-founded the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona. *

He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advocating "pure" photography which favored sharp focus and the use of the full tonal range of a photograph.**************

He developed the Zone System ************ a method of achieving a desired final print through a deeply technical understanding of how tonal range is recorded and developed during exposure, negative development, and printing. ******************* (the bane of my college darkroom education!) **********************

I have always felt conflicted when I think about the work of Ansel Adams. As a little shutterbug, I was in awe of his photos. From a technical standpoint, they seemed an untouchable level of perfection. His subject matter, predominantly his nature landscapes, showed a world (that in hindsight I realize) mesmerized my young eyes with their rendering of the sublime. However, as I went off to art school, I began to realize that the photographic medium encompassed so much more than the world that Adams was showing us. That is when I steered away from the “Ansel Adams Admiration Society.” Of course, some of my attitude was no doubt fueled by the ever-expanding rebellious streak that my college years had fostered and encouraged. I distinctly remember the first time I laid eyes on a Robert Frank photograph and needed much time and thought to reconcile that these two men were working in the same medium, yet their photographs seem so different. Frank’s (and many others’) work appeared far more visceral, energetic and also critical of society. It expanded my perception of what photography could be. And though there is still a place in the world for Ansel Adams, I moved further and further away in my appreciation for his work.

I recently stumbled upon a quote by Thomas Barrow, pulled from an interview that he did with photographer David Ondrik. Barrow’s statement about the work of Ansel Adams really struck a chord with me, finally articulating what I’ve thought about his work.

“Nobody seems to want to be challenged in photography. Maybe it is simply too easy, people want a simple rendition of what they saw at one time or another. A friend wrote, regarding the recent Adams Polaroid auction, to say he just doesn’t get it, that Adams is the greatest 19th century photographer who happened to work in the 20th. Now, Adams was a great guy, great Naturalist, Environmentalist, Martini drinker. But there’s nothing 20th century about his photography. Looking at his photos you wouldn’t know that Impressionism, Futurism, Abstract Expressionism – that there were major changes in the visual arts in the 20th century.”

What really ring true for me really for the first time and thinking about Ansel Adams was Barrow’s point about Ansel Adams being a great 19th century photographer. And looking at his work again after reading this quote I do realize that Adams seem to create his work devoid of any reference to what was going on certainly in the art world also in the photographic world and to some extent what was going on in the real world at the time that he was making his work. The lone photographer out in the wilderness lugging his 4 x 5 camera and tripod on his shoulder is it romantic vision and I wonder if that version or version of a photographer still even exist today. With a Instagram and iPhones everyone’s a photographer of course, and I’m not going to beat that dead horse any further. The dedication to the craft that Ansel Adams exemplified should still garner respect. However, I think that the medium has moved so far beyond what Adams was showing us in his photos, the majesty of nature the pristine landscapes the almost mythical views that he shared with us. I think you could possibly make photos like that still today but my question is: why would you do it? That’s not to say that all art and in general and photography specifically needs to deal with the harsh realities of human life on this dying planets however Adams work in my mind belongs even more so on a postcard or a calendar. Because ultimately those images sure world that in my mind is nothing but a fantasy. One that would be better served by a painter with oils and canvas. The technical achievements that Adams showed throughout his life end up looking like nothing but pretty pictures to my jaded, 21st Century eyes. I’ve heard enough photographers wax poetic about “Moonrise Over Hernandez, New Mexico.” Take a ride through that area today and that “fantastic scene” of a full moon over a sleepy high desert town…well it just feels like about as far from reality as you can get. And trust me, if I hear the origin story of that image one more time, with the legendary “no light meter” hook, I think I’ll drink a warm mug of D-76.

Still, I would be remiss if I did not give some credit to Mr. Adams. He certainly elevated public and collector’s attention towards fine art photography. He also, in some ways, liberated photographers who followed him. No longer did we need to pursue the epic location, the sublime vista, the perfect composition, the sharply focused negative, the full tonal range print. My own reckless abandon… taking sharp blades and flames to my negatives, surely has old Ansel spinning in his grave.

One steaming mug of D-76, please!

I certainly don’t mean to take a hammer and chisel to the feet of a monumental photographer, but at the same time this exploration has given me the opportunity to reassess where Ansel Adams work and reputation belongs. With tongue firmly planted in my cheek, I’ll just say that I won’t be spending any of my cash on an Ansel Adams calendar or coffee mug anytime soon.

“Crowd at Coney Island, July 1940” © Weegee; image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Worth A Thousand Words: Weegee

After over a year of social isolation and staying home, I have recently been feeling the pendulum swing of emotion and desire. Between the desire to get back out into the world (safely vaccinated) and the fear and anxiety of being out around people again. I think I’ve gotten used to my routine of working from home, and the prospect of being part of a large crowd… or even a small one, honestly... is filling me with trepidation. It is in that spirit that I want to take a deep exploration into this historic photograph by the enigma known as Weegee. His real name was Arthur Fellig, but as his self-aggrandizement of adding “The Famous” to his pseudonym was some indication: this was an artist with an ego. Ego was most likely part of what made him a noteworthy photographer in New York of the 1930s – 1950s. Famously shooting at night, and making the crime and violence of the “Big City” his signature subject matter, it is quite the surprise that this particular image above fits into his oeuvre at all. But not only does it fit, it encapsulates so much of New York life in general, and is a perfect vehicle to explore America society in the year before World War II.

Let’s take an overview look at this photograph. It is a summer day, obviously, and the beach is indeed packed. Claustrophobically so, in fact. Coney Island holds a near mythical place in the American mythos, and it perhaps because of this particular image that we have some idea of how it earns that standing. An escape for the masses since the early 20th century, Coney Island was the resort for the “everyman”. While the posh of the past (and present) could afford a retreat to more exclusive resorts, Coney Island was just a subway ticket token away for millions of New Yorkers. This image was created in July of 1940, and if we consider the world, the country, and the city at that time, we came see an overwhelming mass of humanity united in many ways. Also reflective of social and economic stratification that hung over America, as it crawled out of the Great Depression and slowly marched into a world war.

I find it interesting that a huge section of the crowd is actually looking at the camera. I’ve read that Weegee was shouting at the crowd and dancing to get their attention, in order to get large amounts of people to face him for the photograph. I think this adds to the power of the resulting image. You can scan the crowd and examine numerous faces, as opposed to more anonymous bodies engaged in their own personal worlds. We get to study faces, people of all shapes and sizes (but mostly shades of pale skin it should be noted.) Some eyes being shielded by the sun with hands and arms. Some behind sunglasses or the odd hat here and there. Swimsuits of all varieties. Smiles and quizzical looks. Bodies packed in the frame like sardines (a subtitle I’ve seen attached to this image in numerous places.) The crowd stretches off into the distance, completely obscuring the horizon, save for the amusement pier and rides that skirt the upper edge of the frame. The haze (I imagine it as a mix of heat, airborne sweat, pollution and ocean spray) that rides off the right upper edge of the image leads the viewer to believe that there are hundreds more people beyond what we can see.

There are many remarkable things to ponder in this photograph. Through the eyes of a 21st Century, Covid-19 viewer, I find it hard to even image such a scene existing in the present day. Any image that features a crowd of this size (such as looking at pre-pandemic concert or sporting event footage or photos) brings up a gut reaction of anxiety and fear and a general feeling of vulnerability in me. I also think about the actual times that Weegee worked in. In many ways his imagery helped define how collective consciousness accepts what New York looked and felt like back them. The visual of such a working class crowd, overcrowding the easily-accessed beach on a hot, summer afternoon bears a whiff of rose-colored nostalgia, while also making that location seem unpleasant and uninviting to an introvert such as myself. It also speaks to the state of America at that particular time. Slowly emerging from the Great Depression, but economically still hobbled, this kind of day trip getaway was the best that a working class family could hope for. Also in mind, I think about the impending world war brewing on the other side of the Atlantic. The same waters these folks are enjoying in this photo might very well be a future, final resting place for more than a few of them, just a few years later. The innocence presented (at first glance) ultimately gives way to a feeling of darkness to my eyes while I ponder the future of every person who appears within Weegee’s frame. Considering that this photo is now over 80 years old, it is safe to assume that a vast majority of the people in this crowd are now dead and gone. A day of release, of joy, of flirting, of fighting, of drinking and swimming and playing and loving and crying… gone forever but for this photograph.

Weegee went on the be most well-known for his images of crime, murder, fires and such. But what also lurked behind most of his images was the idea that was first presented by earlier photographers such as Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis. We are shown “how the other half lives.” And though Weegee generally showed these lives through a sensationalistic lenses, I still feel a sense of empathy in many of his images. This Coney Island photo is not an indictment of the folks who crowded the beach that day. If anything, it is a celebration of the dignity of the masses, those who made up (and continue to make up) the true fabric and diversity of New York City. The world shown in this 1940 photo might still feel relevant and relatable to many people who might be heading to Coney Island this summer, freed from lock down and isolation, looking for their day in the sun.

footnote: Years later, this image graced the album cover of George Michael, Listen Without Prejudice Vol. 1.

Worth A Thousand Words: Richard Avedon

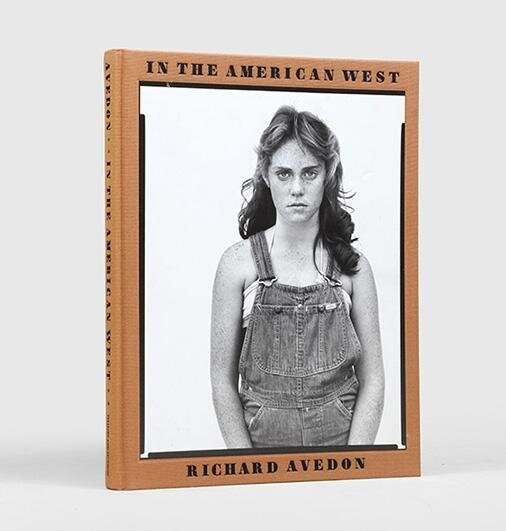

Richard Avedon was probably the most highly regarded fashion photographer from the 1950s through the end of the 1970s. He was also highly regarded as a fine art, portrait photographer. It always seem to me that the two worlds that Avedon worked in were at odds with each other. Yet as I browse through the pages of his seminal book “In The American West” I realize that many of the same techniques that Avedon used to create his signature fashion work is also applied to these “fine art“ portraits.

I looked through this book with more critical eyes recently, with a particular bias against the work; feeling that it is manipulative and exploitative. To my eyes it has a definite agenda of showing a cross-section of the American population of the western states in the early 1980s as a rogues gallery of drifters, laborers and misfits. In some ways, it seems that Avedon is presenting a manipulative freak show to an art world elite.

At same time, as I look through this work, my mind drifts to the work of August Sander, the great portrait photographer of early 20th-century Germany. While similarities exist between the two photographers, there are glaring differences as well. Most obvious to me, there is a deep sense of respect that I feel exists in Sanders’ work that I feel is vacant from the work of Avedon in the American West series. Perhaps Avedon’s choice of using a blank, white backdrop for his series makes the Sander’s photos feel more of the time and place they were taken. Less clinical, more empathetic.

I remember first coming across the “In The American West” book when I was in college in the 1980s. In some ways Avedon’s photos were a revelation. I realized quickly that it explored a whole other America, quite different from the faces and places that I was familiar with in the New York / New Jersey area. There are many memorable portraits in the book, but there is one in particular that still today holds a certain power over me.

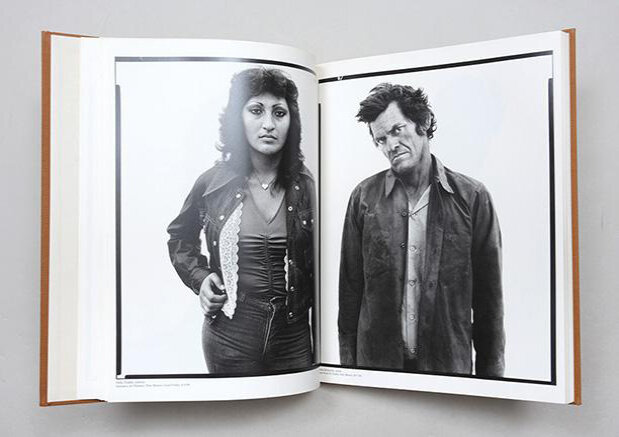

I will focus now on the photo of Carl Hoefert, an unemployed blackjack dealer from Reno, Nevada. The photo is dated August 30, 1983. While I was no doubt celebrating my birthday (most likely with a quart of Budweiser on the bleachers at Berkeley Park in Dumont, NJ) Avedon was setting up his 8 x 10 camera and shooting this intriguing portrait.

photo by Richard Avedon

Avedon’s standard approach shows the subject roughly from the waist up against a white background. The lighting is diffused; there are no sharp shadows. The film edge let us know that this is a sheet of large format film (and as I learned later this was shot with an 8 x 10 camera.) When Avedon traveled around the US west for this project, the camera was attended to by a group of photo assistants. I also learned that Avedon would stand near the front of the camera with the shutter cable release in his hand; having a conversation with his subjects, who did not know exactly when the photograph was being taken.

One of the first things that catches my eye in this portrait of Carl Hoefert is the texture of his face. His weathered skin, his furrowed brow, the wave of his hair, the strong vertical ridges in his neck, the slight clench of his left hand. His right hand gently tucked into a pocket, like someone hiding an ace, perhaps. All are given extraordinary detail thanks to the 8 x 10 camera. Then there is his dress. He’s wearing a striped jacket that features a chevron-like pattern that is at odds with a garishly patterned, polyester shirt. So much texture, so much to read into this appearance, and how it is presented.

As is the case with much of this series, Avedon treats his subject like a specimen, something to be studied and scrutinized. It is also telling that these photos were all printed much larger than life size, all the better to see every unglamorous detail. Because of this, I can’t help but feel that he is taking advantage of (some might say exploiting) his subjects. Case in point: no one ever smiles in Avedon’s portraits. I think this is really important because if Carl Hoefert was smiling I think we would react completely differently to this photograph. Additionally, the fact that he is titled (labelled as) an “unemployed blackjack dealer in Reno” is already skewing our perception of him and again, I think that’s exploiting this person. I don’t feel any empathy coming from the photographer.

At the same time, Avedon’s series is not without merit. Some critics consider the project his magnus opus. He most definitely opened up an unexplored world of “otherness” to an audience to whom the subjects were no doubt unfamiliar; people you might never have come face-to-face with. On the streets of New York City it’s easy to ignore the homeless, the poor, the crazed wanderers, the drifters… society’s casualties. You keep your head down and make your way to wherever it is you’re going. So in some ways, these portraits give us an almost voyeuristic opportunity to stare in the face of someone we would never have the opportunity to stare in the face of in real life. To study and really look, and of course, to judge.

Ultimately, I can’t come to a clear conclusion about this work, and perhaps that’s why it is still carried so much intensity after almost 40 years. The viewer must reconcile our own feelings towards these people, as they stand as evidence of a complex, unvarnished, unromantic America. These people stand as casualties in some way or another, victims of a broken American dream. And it’s this last note that I think really connects with a contemporary viewer, because we know that the gulf between rich and poor, the haves and have nots, has only widened in the years since Avedon worked on this project. Right now on the streets of America’s cities are people who don’t look much different than those portrayed “In The American West.”

Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1957, Garry Winogrand. Image copyright Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery

Worth A Thousand Words: Garry Winogrand

Though he would loathe the distinction, Garry Winogrand was one of the great “street” photographers to have emerged in the late 1950s. He was championed by John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art, but oddly his reputation has faded over the past few decades. I think that photographers such as myself from certain generation know of his work, but his name seems to have been slightly forgotten amongst a younger audience. Which is a shame considering how popular the genre of street photography is today. Going back over his work, especially those created during the height of his powers in the early 1960s, would be an enlightening experience for any young photographer unfamiliar with his body of work. Admittedly, some of Winogrand’s work has not aged well. Especially his series titled “Women Are Beautiful.” This specific work feels very different when viewed from a contemporary standpoint compared to the times when they were originally created; one could argue against this kind of “photographic male chauvinism.” For some context, I highly recommend viewing the documentary film which came out last year “Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable” by Sasha Waters Freyer.

There is one photograph in particular by Garry Winogrand that has stayed firmly in the back of my mind since I most likely first gazed upon it as a young photo major in college. Growing up in New Jersey, I had a somewhat narrow view of the world for sure and my impression or imagination of what the rest of the world or even the rest of the United States might look like was shaped primarily via television, movies and especially, photography. The image that I am focusing on today by Winogrand was taken in Albuquerque, New Mexico In 1957. Little did I know when I looked at that photo for the first time that I would eventually find myself living in New Mexico. That photo really shaped what I thought this place might look like, having never visited it.

So looking at this photograph what do we see? The outer edge of some tract home. A garage door is open. In the darkness a child stands in the back, while right at the threshold of the garage, lit by bright sunlight is an infant… walking out into the world… arms partially outstretched. The driveway is sectioned cement. An oil stain appears about a third of the way down and closer in the foreground is a small tricycle on its side. As we looked to the other half of the photograph, we see barren desert stretching off to a mountainous horizon. Storm clouds appear over the mountains, and a white letter “U” is seen against the mountain (most likely representing the University of New Mexico.) The desert scrub that extends up to where this house sits is punctuated in the lower corner of the photograph by a small shrub… possibly a cactus or some other native desert plant.

There are many things I find compelling about this photograph, regardless of the fact that I live a few miles away from where it was taken. It was shot in 1957, the times were the height of Eisenhower era, post-WWII boom. The middle class was continue to expand, and the west (or in this case, southwest) was experiencing a population burst, thanks in large part to the expanding interstate highway system, the ubiquitous automobile and the availability of cheap land to fill up with suburban housing. This is all apparent in this photo by Winogrand. What I find though, against a manufactured backdrop of optimism, there is a dark sense of foreboding emanating from this scene. The storm cloud, of course, brings a degree of menace to the environment. There are other clues. The tricycle on its side, a hazard to a driver, perhaps. A potential cause of injury for the boy in the background? The two children are unattended. Perhaps not a shocking then as it would most likely be to contemporary parents, but odd that a stranger with a camera could roll up and shoot this photo. What else could a passing stranger be capable of here? And this house… on the edge of a development, with nothing but open desert at its side. What potential threats linger just a few feet away from this house? As many of us who live in the desert know, it is a dangerous place. It would be too easy for a child to wander off, get lost, fall into a dry river bed, stumble into a thorny plant, or perhaps encounter an animal or a reptile that could easily inflict harm.

The fact that this house appears to sit at the far edge of humanity is quite striking to my eyes, as I know the part of the city where the house is located. In the 60 plus years since the image was created, huge amounts of development have occurred in Albuquerque, and the entire area of the city where this house sits is unrecognizable from how we see it here. The majesty of the Sandia Mountains shown off in the distance would be completely obscured if one were attempting to recreate this photo today. While, in the other direction on the outer edges of Albuquerque West Side, one could find, I’m sure, the 21st Century equivalent of the scene Winogrand stumbled upon back in 1957.

The same house, 60 + years later.

Out of curiosity, I decide to try to find this location for myself. And thanks to some internet sleuth work, I did indeed find it (thank you Google Maps.) On a non-descript side street in the Northeast Heights of Albuquerque, sits the original house from the photo. It still has some of its characteristic details, most specifically the concrete driveway, the front windows along the left side of the image, and the telltale beam along the right side of the garage (though the house numbers are long gone, the front curb has the numbers 1208 spray painted on it.) As you can see, the sweeping view of the mountains is gone now, blocked by a neighboring house, although there is a tiny bit of the range still visible just beyond the backyard fencing. I experienced a kind of self-induced déjà vu while standing in front of the house. I was waiting for someone to walk by and acknowledge the significance of the location. Alas, only the midday sun and a slight springtime breeze provided whatever pinch of reality the location was able to muster.

A scene from "Palermo Shooting" a film by Wim Wenders

On Photography and Death: Palermo Shooting

This week will be at departure from my usual 1000 words series. I usually write about one specific photograph. Instead, this entry will be my reflections on the Wim Wenders film, Palermo Shooting. The film was released in 2008 (apparently garnering a chorus of “boos” when premiered at Cannes) but I only saw it for the first time this week, thanks to my new subscription to Filmstruck. I won’t go into the deep cinema geekdom that pushed my decision to join Filmstruck except to say that having so many great movies at my disposal is an embarrassment of riches.

The story of Palermo Shooting revolves around the main subject named Finn. The character seems based on German photographer Andreas Gursky, as has been noted in several reviews that I read. Fill is played by Die Toten Hosen lead singer, Campino. Finn is a highly successful photographer who is creatively torn between the moneymaking pursuit of fashion photography and the less lucrative but more fulfilling artistic photography route. He is seemingly lost in the void between the two. A near death experience on a highway in Germany causes Finn to reassess his career and in a larger sense, his entire existence. He ends up in this Sicilian capital of Palermo, where his reality and dreams blur, not only before his eyes but before the eyes of the film’s viewer as well.

The reason why I am exploring this film is that photography is an integral part of the storyline. Wenders has always imbued a photographic sensibility into his highly cinematic motion pictures. As evidenced by the current exhibition of his Polaroid photographs now on view in London, one can see that the director’s deep love and devotion to the medium of still photography is obvious. The fact that Palermo Shooting focuses on a main character who is a photographer is more noteworthy when we take deeper into the real subject of the film, which is the confrontation of death

Susan Sontag in her book “On Photography” speaks eloquently of the medium’s connection with death.

"Photographs instigate, confirm, seal legends. Seen through photographs, people become icons of themselves. Photography converts the world itself into a department store or museum-without-walls in which every subject is depreciated into an article of consumption, promoted into an item for esthetic appreciation.”

“Photography also converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also — wittingly or unwittingly — the recording-angels of death. The photograph-as-photograph shows death. More than that, it shows the sex-appeal of death…All photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

Noted philosopher Roland Barthes also explored this topic in depth in his book “Camera Lucida.”

“All those young photographers who are at work in the world, determined upon the capture of actuality, do not know they are agents of Death. This is the way in which our time assumes Death… For Death must be somewhere in society; if it is no longer (or less intently) in religion, it must be elsewhere; perhaps in this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life. Contemporary with the withdrawal of rites, Photography may correspond to the intrusion, in our modern society, of an asymbolic Death, outside of religion, outside of ritual, a kind of abrupt dive into literal Death. Life / Death: the paradigm is reduced to a simple click, the one separating the initial pose from the final print.”

Dennis Hopper as "Death" in Wim Wenders' "Palermo Shooting"

In Palermo shooting, Wenders also addresses this issue. In a particularly powerful moment the character representing Death, played wonderfully by Dennis Hopper, meditates on the intrinsic qualities of death in photography in the following statement.

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against photography. I’m actually very fond of that invention. It shows the efforts of my labor better than anything else. “Death at Work.” That’s what most still photographs should be called. I really like the idea of the negative, the reverse side of life. The reverse side of light.”

This moment in the film struck a nerve deep inside of me personally. I have often considered that a photograph is in some way a “memento mori.” Even a simple snapshot, whether viewed in a photo album, as in day’s past, or more likely in today’s world, on a Facebook page, contains elements of sadness, and loss. A photo of smiling family, seen enjoying a candid moment, takes on a darker subtext when considered that this will be evidence of a life that no longer exists once those in the photo have passed away.

In Palermo Shooting, Wenders is overt in this exploration of photography’s intrinsic deference to death. A quick search of movie reviews will yield much evidence of what is almost unanimously considered the directors ham-fisted, obvious, unsuccessful story of a man’s confrontation with his own impending death. However, perhaps it is because of the Sicilian blood that still flows through my veins (thanks to my ancestors) that I felt an affinity with this film.

Some of the most dramatic scenes in the film were the haunting dream sequences. This includes several scenes that were shot in the macabre catacombs underground Palermo. Wenders obviously was using the location of the Sicilian capital as ground aero for the realm of the dead. Some might argue that that title more rightly should go to the city of Naples. But for me these are minor issues.

Another aspect of the film that appeal to me directly, and most likely to you, as a photography enthusiast, is the obvious camera porn on display. The main subject, Finn, is seen throughout the film shooting with a beautiful Japanese medium format camera, the Plaubel Makina 67. There are also several scenes where he is shooting with a 360° panoramic camera, including a pivotal moment in the film where it almost leads to his demise. And perhaps the most touching moment of the film is when Finn crosses paths with noted Palermo photographer Letizia Battaglia. She is seen shooting a Leica and has a heartfelt exchange about the subjects of photography and death with our hero.

Ultimately, Palermo Shooting is far from Wim Wenders’ best work. His pinnacle remains “Wings of Desire,” though one could make a strong argument for “Paris, Texas.” However, if you have the desire to watch one man’s journey towards the acceptance of his own demise, shown through the viewfinder of photographic expression, devoting two hours of your time to this movie is well worth the investment.

photo © Sally Mann

Worth A Thousand Words: Sally Mann

Portraiture has always confounded me. As a photographer, I’ve struggled when I’ve had to deal with actual human beings as subject matter. Especially when they are directly in front of me, posing for a formal portrait. I am just unable to capture the essence of a person through a photograph. That’s not to say that I don’t ever take pictures of people. It’s just that they tend to be in an environment, usually on the street, or part of a larger, more complex scene. At the same time, as a viewer, I am constantly drawn to a great photographic portrait. Needless to say that our western pop culture is awash in portraits, many focusing on those in power, or those with celebrity. Add to the mix the current frenzy of selfies clogging up social media platforms, and one could deduce that perhaps we’ve hit the breaking point where the whole idea of a photographic portrait has transformed into something other than a thoughtful study of not just the appearance of the subject, but also a deeper exploration of their mood, their character, their psychological makeup. Most portraits today, to my eyes, seem more self-aggrandizing, self-serving; propaganda mechanisms more than anything else.

With this cynicism in mind, I focus my gaze today on a most beautiful portrait. Titled “Black Eye” it is by a true American master, Sally Mann. Sally Mann has made a career of photographing her immediate family, most notably her children. This approach has brought her much acclaim, but also much criticism. The critics are usually from outside the photography / art worlds. The puritanical, religious “moral police” that exists in the United States have, on numerous occasions, worked themselves into a foaming-mouth frenzy over the intimate work of Mann. Their objections are almost always due to the fact that Mann has no reservation for showing her (then) young children, both male and female, in the nude. The rabid critics have dismissed the work and pornographic at worst, exploitative of innocence at best.

The image I am discussing today is of a fully clothed child, the artist’s daughter, but still has been cause for alarm by many narrow-minded critics. More on that in a few moments. Let’s take a closer look at the photograph. It is a black and white image. A young girl sits in an antique looking chair, and is positioned squarely in the middle of the frame. Her eyes are closed, her arms are crossed. She is bathed in wonderful, soft natural light, coming from a window that is in the distance, the edge shown in the photo, out of focus. The hair on the girl looks like it has been blown to the side by a sudden soft breeze. The focus on this image is interesting to me. The detail on the white lace below her neck indicates a shallow depth of field. The hair and chair shows a varying degree of focus as well. The curls of hair along the lower neck is a foil to the unkemptness of the blown hair along the top of her head. Her hands are crossed, but at ease, and they look as though they are cradling something. The wonderful downslope of her dark lips brings a certain melancholy to her appearance. And then we have the black eye. How did this happen? The zealot critics have projected evidence of child abuse onto the photo. But as we know, kids get all sorts of bumps and bruises while the explore their world. And I can help but think that her eye looks swollen due to a bug bite. Especially when you consider that Mann and her family live in rural Virginia, there are all sorts of reasons a child might be sporting a swollen, black eye.

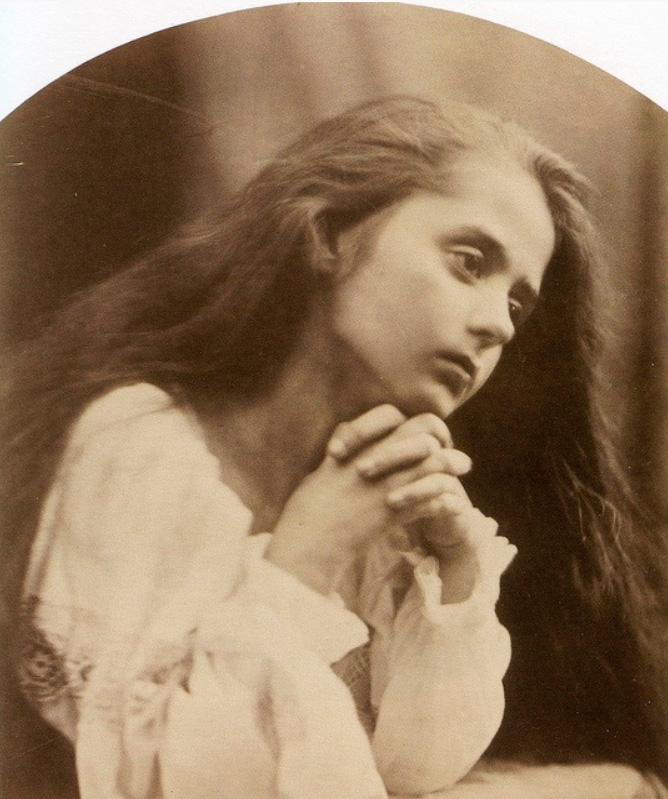

Photos by Julia Margaret Cameron

What I find most striking about this image is its timelessness. It looks like it could have been made in the later 1800s, and reminds me of the work of Julia Margaret Cameron, with its references to Pre-Raphaelite painting, featuring limp poses and soft lighting. Mann’s photo has the same qualities. The young girl’s dress furthers this timeless atmosphere, as does the chair she sits in. The photographer has captured not only a very intimate moment, but has, though her craft, imbued the image with so much psychological power. The photo not only seems to represent a girl lost in a dream, but also feels like a dream itself. And if I dive further in the subconscious elements seen here, I could also see this as a death portrait. Her eyes are closed, her hands are crossed. Is she laid out in a coffin? Is this a display, not only to the fleeting nature of youth, but the ever present spectre of death? Now consider that this photograph was taken by the girl’s mother. The sense of serenity is one that a mother would probably know better than anyone, when seeing your young child asleep. But isn’t also a parent’s greatest fear, the death of their child? Is Mann exploring this fear with her camera? Is she challenging the viewer to take stock of their own familial relationships? Could a stranger had been able to create such a powerful image of the same young girl? I doubt that the kind of gentle touch of the artist’s lens, the intimacy of the space, the softness of the light would be available to an outsider.

It is a sad fact that women are underrepresented in the arts, and photography is no exception. Men have most times taken the spotlight as innovators, or as the heroic masters of the art world, and certainly this holds true in photography as well. But it is the work of Sally Mann that proves the value, the legitimacy and the true artistry that a woman artist can possess, and should rightfully be recognized for. I would highly recommend reading Sally Mann’s autobiography, “Hold Still.” Her family history certainly informed her artistic development, but it’s also a wonderful look at the creative process of a true photographic master.

Photo © Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Worth A Thousand Words: Bruce Davidson

Time to jump back into my series of blog posts that take a closer look at some iconic photographs. Today, I'm looking at and discussing the work of Bruce Davidson. Specifically, an image that graced the cover of his landmark book of color photographs titled "Subway."

To begin, let's take a trip back in time to the 1970s in New York City. The city was a dangerous place. Crime was rampant, blight was everywhere, and when to city declared it was nearing bankruptcy, the message received from then President Gerald Ford was "Drop Dead."

As the Rolling Stones sang "bite the Big Apple, don't mind the maggots," the denizens of the city went about their daily lives, which for many included a daily descent into the graffiti covered subway system. If there was one thing that best represented the sad state of urban life in 1970s NYC, it was the filthy, crime ridden train system. It was into this world that acclaimed Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson descended as he embarked on a project that would become a landmark book of color photographs.

Davidson was no stranger to the streets of New York City. He had been shooting street gangs and poor neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs for some time. In the preface for the "Subway" book, he discusses how dangerous it was to be working alone in this subterranean environment. He had equipment stolen and had been harassed when he got too close to certain subjects or situations. Yet, he was driven to explore the world that existed below street level, and persisted to create a truly stunning body of work.

Up to this point, most of Davidson's previous work had been shot in black and white. The decision to shoot color for the Subway project was a wise choice. The different sources of light, both natural and artificial, the variety of skin tones and clothing color palettes, the smattering of spray painted graffiti... these needed to be seen in full color.

“I wanted to transform the subway from its dark, degrading, and impersonal reality into images that open up our experience again to the color, sensuality, and vitality of the individual souls that ride it each day.”

The image that I'd like to spend time discussing in further detail happens to be the cover image from the book. So, what do we see? A color image, shot inside a subway car. The composition is solid, with the main subject, a shirtless man, slightly off center, and rows of florescent lights angling down on either side of him, pulling the viewer's attention right to the middle of the frame. We then can focus our gaze on the gold necklaces hanging around the man's neck, with a cross sitting squarely in the middle of his muscular chest. The man's face is obscured in shadow, but we can clearly make out a mustache above his upper lip. Judging by his skin tone, and the religious jewelry, I am making the assumption that he is a Hispanic male, most likely in his late teens or early 20s.

Firstly, what I find striking about this image is how close to his subject Davidson got to take this photo. It was surely shot with a wide-angle lens, so I would guess that he was standing within a foot or so of his subject. This is no "on the sly" hipshot. The subject certainly knew he was being photographed. What makes this image so intriguing to me is when I start to consider who this shirtless man may be, what kind of personality might he possess? He has the machismo to be riding the subway shirtless, which is a bold statement of non-conformity and a disregard of the likely rules against doing so. He is also showing off jewelry that I'm sure has some monetary value. One would think a quick grab from a thief would garner items that could be sold on the street for a decent amount of cash. However, who would dare make this kind of move? Is the shirtless man challenging those around him with this kind of flaunting? Is he daring other to try to make a move on him? Is there any irony in the fact that he is showing symbols of his religious faith in an environment that many would argue is devoid of God's presence?

I would guess that many riders in that particular subway car were averting their eyes from this man, as most New Yorkers will tell you is one way to survive in the city... never make eye contact with anyone. Davidson is doing almost the same thing here. We don't actually see the man's eyes. They are mostly hidden. Yet, the photographer does not shy away from a different kind of confrontation in this picture. He did not turn away, but instead took the photo. This is creative bravery on display.

Again, I must revisit the fact that this image was shot on color film. As much as I prefer to shoot in black and white for most of my own work, I do recognize that there is a time and a place for color photographs. I doubt that this Bruce Davidson photo would have the same impact if it were shot in black and white. The beautiful skin tones that inform so much, the pop of the gold chains, the sickly bluish green of the rows of florescent lights, the cool chrome of the straps; all gain so much by being seem in glorious color.

I highly recommend Bruce Davidson's book "Subway" to any lover of street photography. It is work that utilizes the documentary style that earned him a place along the other masters of Magnum, but merges it will a more artistic exploration of light and color. And it harkens back to the pre-Giuliani days when New York City was a seedy, dangerous, yet still exciting place to venture. The days when a quasi-vigilante group like the Guardian Angels were seen as a sensible reaction to the crime filling the streets and the subways. Maybe the good old days were a bit closer to bad old days, but something was definitely lost as the city cleaned itself up.

Photograph © 1958 by Robert Frank

Worth A Thousand Words: Robert Frank

Up to this point, I’ve been hesitant to write any words about Robert Frank, for a number of reasons. Most of them are rooted in my deep love of his work and the profound influence he has had on my own image making. How do I pay due respect to an artist so important to me? Can I be objective when writing about a particular image of his? Another challenge would be deciding which of his images would I focus my attention on? There are just too many touchstone Robert Frank photographs to choose from. Nonetheless, with a looming exhibit of my own, it made sense to try to write about this week’s image “Covered Car, Long Beach, California.”

So, what do we see in this photograph? It is a car, covered in some kind of white fabric. The car is parked between two thick palm trees. Shadows from the trees are cast upon a plain looking, boxy building, the wall of which look covered in a dark stucco. The light seems like late afternoon to me. The composition is slightly off kilter, just slightly tilting to the right. The fabric that covers the car has an almost striped appearance to it, the result of bands that are stitched together. The contrast is somewhat stark, with the white of the cover offset by the deep shadows on the wall, and the tufts of palm leaves on the trees. All in all, a fairly non-complex photograph at first glance.

What is not seen in the photo? Well, this is an urban environment, but there are no people seen in the shot. And we of course assume there is a car under the tarp, being able to recognize the shape of the chassis, and the distinct poke of an antenna pushing up the covering as well. The next question I ask myself is why did Frank take this photo? It appears in his seminal book “The Americans” which creates a context for a deeper interpretation of the image. Frank explored the subject matter of the automobile extensively throughout the book. When Frank was shooting the photographs that eventually became "The Americans," the automobile was seen as a key component to the post-WW2 westward expansion in the United States, and was a symbol of freedom and mobility for a growing middle-class society. The fact that the car is covered brings what seems to me an elegiac quality; quite a mournful feeling to this image. Coupled with the fact that the lighting indicates late in the day, nearing sunset, I get a distinct feeling that there is an intrinsic sadness to this image. The car becomes a body covered, something to be mourned, hidden, and prepared for some kind of death. Of course, this is my personal projection on to the image, but if an astute viewer were to look at the photo in the context of where it appears in “The Americans” one would make a similar leap.

The image appears in a sequence of the book that begins with a close up, side view of two men in the front seat of a car, “US 91, leaving Blackfoot, Idaho.” Here we see the car as a means of escape, with Frank a passenger in a very tight front seat with two mean who look as though the are fleeing a crime scene. Next is an image of five elderly people sitting on a roadside bench, titled “St. Petersburg, Florida.” In the background, we see a car speeding by, slightly blurred. Is this a rumination on death, the life that is soon to be leaving these people speeding behind them as they wait for the inevitable? The “covered car” photo is the next image in the sequence. The photo that then immediately follows shows the aftermath of a car accident, with a group of four people standing beside the blanket covered remains of what is surely a dead body. The covered body echoing the covered par in the previous image. To complete this run of images, we see a long view of a lonely highway in New Mexico, stretching off into the far distance, with just a lone car driving towards us, seen very far off in a dark, foreboding environment, under a threatening sky. Seen as a whole, this sequence of images tells a sad story of life and death intertwined with the presence or influence of the automobile.

Photograph © 1958 by Robert Frank

My own fascination with covered cars stems directly from the image made by Robert Frank. My approach to the subject matter is quite different. For one, I chose to show the cars in color. I have taken a clinical, studied approach to the subject matter, and have assembled well over fifty of such images, to date. I am fascinated when I look at them as a group of photos, when the variety of covers and locations become a foil to the consistency of the subjects. Yet, there is still that initial feeling of sadness that permeates the images I make. These vehicles are covered for reasons I don’t ever really know. Are they classic cars that require protection from the elements? Are the windows busted and leaking, requiring covering to protect the interior? Is the vehicle evidence of some crime? Has an accident occurred? They often look like Christ-like bodies, covered in shrouds. Or perhaps they represent something desirable yet hidden from view, their covering providing a layer of mystery and intrigue.

It is amazing to me that so many of these covered cars reveal themselves to me as I travel my home city, but also in locations that I travel to. They seem to be everywhere once I start looking for them. They serve as a constant reminder of the influence that Robert Frank has had on my work, and send a silent message of kinship and solidarity to me as I pursue my work. As the master has said, “The eye should learn to listen before it looks.” I am constantly listening and looking, too.