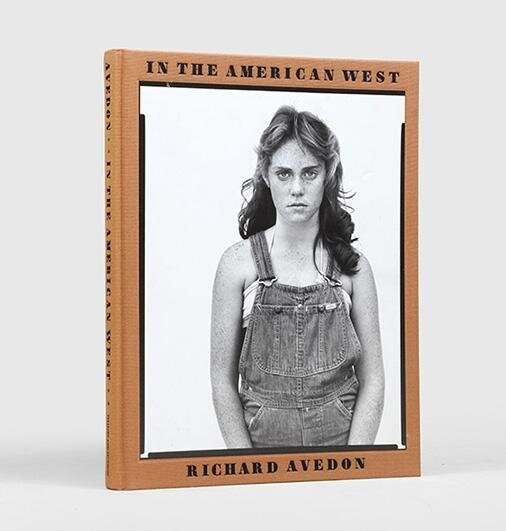

Richard Avedon was probably the most highly regarded fashion photographer from the 1950s through the end of the 1970s. He was also highly regarded as a fine art, portrait photographer. It always seem to me that the two worlds that Avedon worked in were at odds with each other. Yet as I browse through the pages of his seminal book “In The American West” I realize that many of the same techniques that Avedon used to create his signature fashion work is also applied to these “fine art“ portraits.

I looked through this book with more critical eyes recently, with a particular bias against the work; feeling that it is manipulative and exploitative. To my eyes it has a definite agenda of showing a cross-section of the American population of the western states in the early 1980s as a rogues gallery of drifters, laborers and misfits. In some ways, it seems that Avedon is presenting a manipulative freak show to an art world elite.

At same time, as I look through this work, my mind drifts to the work of August Sander, the great portrait photographer of early 20th-century Germany. While similarities exist between the two photographers, there are glaring differences as well. Most obvious to me, there is a deep sense of respect that I feel exists in Sanders’ work that I feel is vacant from the work of Avedon in the American West series. Perhaps Avedon’s choice of using a blank, white backdrop for his series makes the Sander’s photos feel more of the time and place they were taken. Less clinical, more empathetic.

I remember first coming across the “In The American West” book when I was in college in the 1980s. In some ways Avedon’s photos were a revelation. I realized quickly that it explored a whole other America, quite different from the faces and places that I was familiar with in the New York / New Jersey area. There are many memorable portraits in the book, but there is one in particular that still today holds a certain power over me.

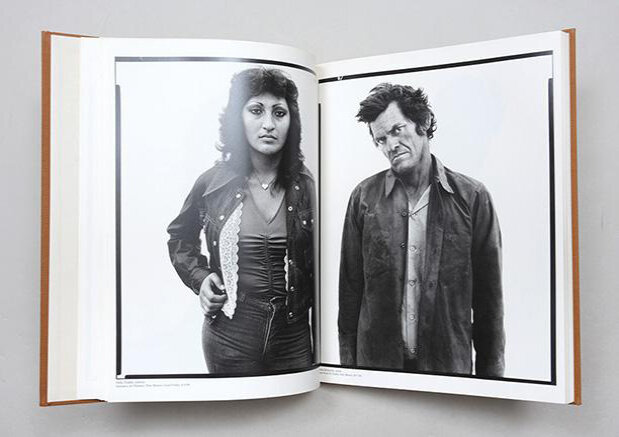

I will focus now on the photo of Carl Hoefert, an unemployed blackjack dealer from Reno, Nevada. The photo is dated August 30, 1983. While I was no doubt celebrating my birthday (most likely with a quart of Budweiser on the bleachers at Berkeley Park in Dumont, NJ) Avedon was setting up his 8 x 10 camera and shooting this intriguing portrait.

photo by Richard Avedon

Avedon’s standard approach shows the subject roughly from the waist up against a white background. The lighting is diffused; there are no sharp shadows. The film edge let us know that this is a sheet of large format film (and as I learned later this was shot with an 8 x 10 camera.) When Avedon traveled around the US west for this project, the camera was attended to by a group of photo assistants. I also learned that Avedon would stand near the front of the camera with the shutter cable release in his hand; having a conversation with his subjects, who did not know exactly when the photograph was being taken.

One of the first things that catches my eye in this portrait of Carl Hoefert is the texture of his face. His weathered skin, his furrowed brow, the wave of his hair, the strong vertical ridges in his neck, the slight clench of his left hand. His right hand gently tucked into a pocket, like someone hiding an ace, perhaps. All are given extraordinary detail thanks to the 8 x 10 camera. Then there is his dress. He’s wearing a striped jacket that features a chevron-like pattern that is at odds with a garishly patterned, polyester shirt. So much texture, so much to read into this appearance, and how it is presented.

As is the case with much of this series, Avedon treats his subject like a specimen, something to be studied and scrutinized. It is also telling that these photos were all printed much larger than life size, all the better to see every unglamorous detail. Because of this, I can’t help but feel that he is taking advantage of (some might say exploiting) his subjects. Case in point: no one ever smiles in Avedon’s portraits. I think this is really important because if Carl Hoefert was smiling I think we would react completely differently to this photograph. Additionally, the fact that he is titled (labelled as) an “unemployed blackjack dealer in Reno” is already skewing our perception of him and again, I think that’s exploiting this person. I don’t feel any empathy coming from the photographer.

At the same time, Avedon’s series is not without merit. Some critics consider the project his magnus opus. He most definitely opened up an unexplored world of “otherness” to an audience to whom the subjects were no doubt unfamiliar; people you might never have come face-to-face with. On the streets of New York City it’s easy to ignore the homeless, the poor, the crazed wanderers, the drifters… society’s casualties. You keep your head down and make your way to wherever it is you’re going. So in some ways, these portraits give us an almost voyeuristic opportunity to stare in the face of someone we would never have the opportunity to stare in the face of in real life. To study and really look, and of course, to judge.

Ultimately, I can’t come to a clear conclusion about this work, and perhaps that’s why it is still carried so much intensity after almost 40 years. The viewer must reconcile our own feelings towards these people, as they stand as evidence of a complex, unvarnished, unromantic America. These people stand as casualties in some way or another, victims of a broken American dream. And it’s this last note that I think really connects with a contemporary viewer, because we know that the gulf between rich and poor, the haves and have nots, has only widened in the years since Avedon worked on this project. Right now on the streets of America’s cities are people who don’t look much different than those portrayed “In The American West.”