Preface: For those of you who followed my “Worth a Thousand Words” series, you know I usually focus on one specific photograph by a photographer and then take a deeper dive, exploring not only what the image shows but also what the photographer may have been trying to tell us, or have us think about. But for this installment, I’m going to try things a little differently and talk about one photographer and his work (and reputation) in a more general sense. Warning: some of my words may be perceived as inflammatory or disrespectful or antagonistic, all of which may indeed be true.

The God of sharpness, perfect exposure, cable releases and beard grooming

Photo credit: J. Malcolm Greany, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

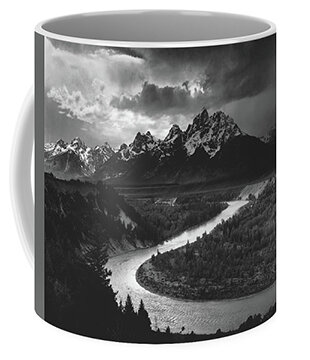

Today, I’d like to discuss the work of Ansel Adams. He is most likely the most well-known photographer in the history of the genre. He is held in high regard by many people, photographers and non-photographers alike. His work can be seen in many formats: not just impeccably printed photographs framed on a museum wall but also in books, calendars, postcards, coffee mugs, refrigerator magnets… I could go on, but I’ll stop there. My motivations for discussing Ansel Adams is rooted in a paradox in my own mind regarding his importance to the art form and his position in the canon of the fine art photography.

I won’t go too deeply into his biography, you can head over to Wikipedia for that. Instead, here’s a list of his achievements. I’ll mark the ones I have a problem with using my newly patented star system.

One * means… a-ok or not so bad.

The more ****s, the more something bugs me.

Ansel Adams was an American photographer and environmentalist, known for his black-and-white images of the American West. *

He was a life-long advocate for environmental conservation *

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980. (from Jimmy Carter, so that’s cool.) *

Adams was a key advisor in establishing the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an important step in securing photography's legitimacy. *

He helped found the photography magazine Aperture. *

He co-founded the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona. *

He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advocating "pure" photography which favored sharp focus and the use of the full tonal range of a photograph.**************

He developed the Zone System ************ a method of achieving a desired final print through a deeply technical understanding of how tonal range is recorded and developed during exposure, negative development, and printing. ******************* (the bane of my college darkroom education!) **********************

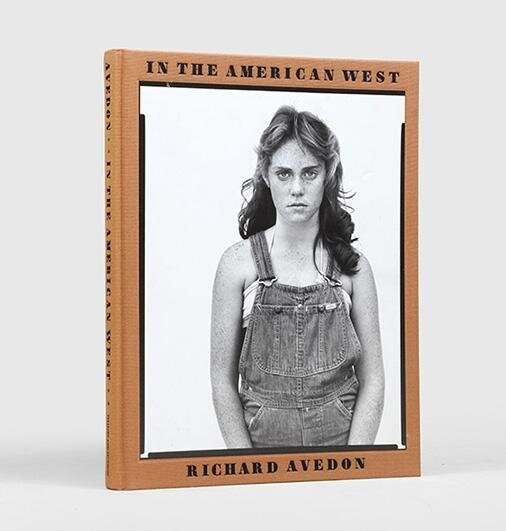

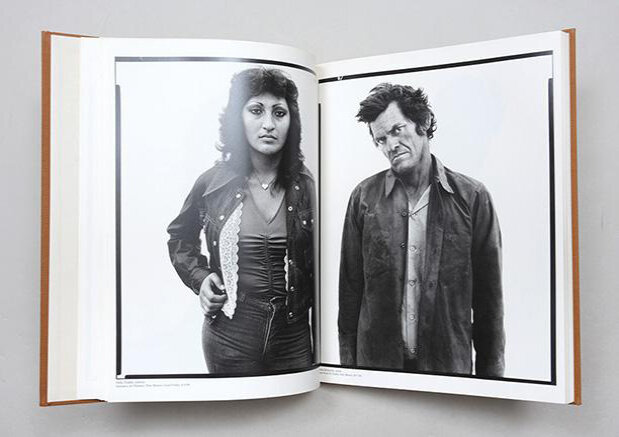

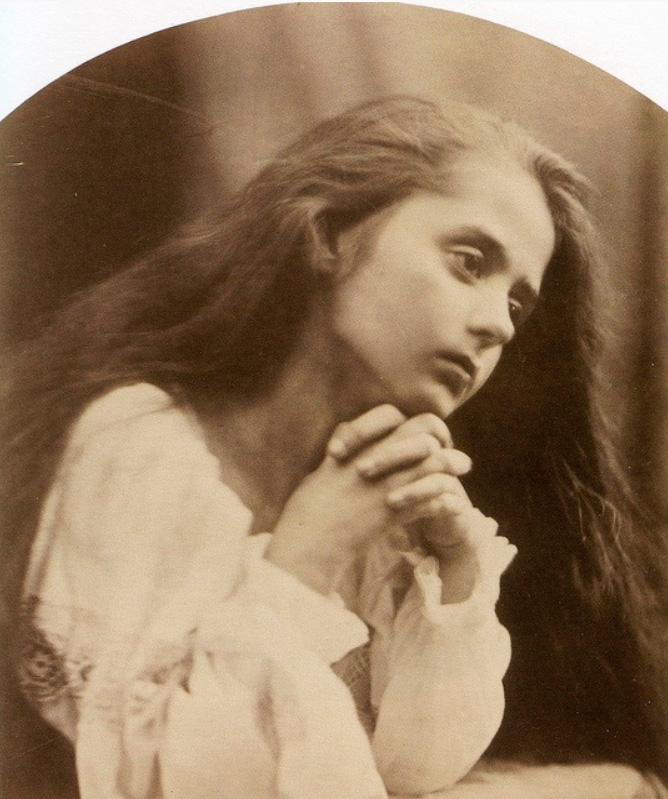

I have always felt conflicted when I think about the work of Ansel Adams. As a little shutterbug, I was in awe of his photos. From a technical standpoint, they seemed an untouchable level of perfection. His subject matter, predominantly his nature landscapes, showed a world (that in hindsight I realize) mesmerized my young eyes with their rendering of the sublime. However, as I went off to art school, I began to realize that the photographic medium encompassed so much more than the world that Adams was showing us. That is when I steered away from the “Ansel Adams Admiration Society.” Of course, some of my attitude was no doubt fueled by the ever-expanding rebellious streak that my college years had fostered and encouraged. I distinctly remember the first time I laid eyes on a Robert Frank photograph and needed much time and thought to reconcile that these two men were working in the same medium, yet their photographs seem so different. Frank’s (and many others’) work appeared far more visceral, energetic and also critical of society. It expanded my perception of what photography could be. And though there is still a place in the world for Ansel Adams, I moved further and further away in my appreciation for his work.

I recently stumbled upon a quote by Thomas Barrow, pulled from an interview that he did with photographer David Ondrik. Barrow’s statement about the work of Ansel Adams really struck a chord with me, finally articulating what I’ve thought about his work.

“Nobody seems to want to be challenged in photography. Maybe it is simply too easy, people want a simple rendition of what they saw at one time or another. A friend wrote, regarding the recent Adams Polaroid auction, to say he just doesn’t get it, that Adams is the greatest 19th century photographer who happened to work in the 20th. Now, Adams was a great guy, great Naturalist, Environmentalist, Martini drinker. But there’s nothing 20th century about his photography. Looking at his photos you wouldn’t know that Impressionism, Futurism, Abstract Expressionism – that there were major changes in the visual arts in the 20th century.”

What really ring true for me really for the first time and thinking about Ansel Adams was Barrow’s point about Ansel Adams being a great 19th century photographer. And looking at his work again after reading this quote I do realize that Adams seem to create his work devoid of any reference to what was going on certainly in the art world also in the photographic world and to some extent what was going on in the real world at the time that he was making his work. The lone photographer out in the wilderness lugging his 4 x 5 camera and tripod on his shoulder is it romantic vision and I wonder if that version or version of a photographer still even exist today. With a Instagram and iPhones everyone’s a photographer of course, and I’m not going to beat that dead horse any further. The dedication to the craft that Ansel Adams exemplified should still garner respect. However, I think that the medium has moved so far beyond what Adams was showing us in his photos, the majesty of nature the pristine landscapes the almost mythical views that he shared with us. I think you could possibly make photos like that still today but my question is: why would you do it? That’s not to say that all art and in general and photography specifically needs to deal with the harsh realities of human life on this dying planets however Adams work in my mind belongs even more so on a postcard or a calendar. Because ultimately those images sure world that in my mind is nothing but a fantasy. One that would be better served by a painter with oils and canvas. The technical achievements that Adams showed throughout his life end up looking like nothing but pretty pictures to my jaded, 21st Century eyes. I’ve heard enough photographers wax poetic about “Moonrise Over Hernandez, New Mexico.” Take a ride through that area today and that “fantastic scene” of a full moon over a sleepy high desert town…well it just feels like about as far from reality as you can get. And trust me, if I hear the origin story of that image one more time, with the legendary “no light meter” hook, I think I’ll drink a warm mug of D-76.

Still, I would be remiss if I did not give some credit to Mr. Adams. He certainly elevated public and collector’s attention towards fine art photography. He also, in some ways, liberated photographers who followed him. No longer did we need to pursue the epic location, the sublime vista, the perfect composition, the sharply focused negative, the full tonal range print. My own reckless abandon… taking sharp blades and flames to my negatives, surely has old Ansel spinning in his grave.

One steaming mug of D-76, please!

I certainly don’t mean to take a hammer and chisel to the feet of a monumental photographer, but at the same time this exploration has given me the opportunity to reassess where Ansel Adams work and reputation belongs. With tongue firmly planted in my cheek, I’ll just say that I won’t be spending any of my cash on an Ansel Adams calendar or coffee mug anytime soon.